Tradecraft Without Thinking

How U.S. Intelligence Education Keeps Producing Analysts Who Can’t Reason Their Way Out of a Paper Bag

When “critical thinking” is a buzzword, “tradecraft” becomes ritual—and the nation pays for it. ~ Dr. Charles Russo

Abstract

U.S. intelligence education and training institutions routinely claim to cultivate “critical thinking,” yet their systems of instruction too often produce analysts who can recite processes, run checklists, and name structured analytic techniques while lacking the deeper intellectual equipment to reason under uncertainty, interrogate knowledge claims, and resist manipulation in an adversarial information environment. This article argues that the prevailing education-and-certification ecosystem treats critical thinking as a competency statement rather than a disciplined practice grounded in logic, epistemology, rhetoric, and ethics. The result is a professional culture that confuses method with judgment, technique with truth-seeking, and compliance with competence—despite formal mandates that elevate analytic rigor and critical thinking across the Intelligence Community. Drawing on public directives and primers, intelligence-failure commissions, and scholarship on intelligence education and tradecraft, the article identifies systemic incentives that sideline philosophy and offers practical reforms: curriculum redesign, assessment modernization, instructor standards, and training evaluation frameworks.

Keywords: intelligence education, analytic tradecraft, critical thinking, epistemology, logic, philosophy, structured analytic techniques, professionalization, intelligence failure, disinformation resilience

Introduction

Let’s be blunt: the U.S. intelligence education-and-training apparatus has spent decades pretending that “critical thinking” is something you can declare into existence with a directive, sprinkle into a slide deck, and then certify with a multiple-choice exam. The system loves the language of rigor—“standards,” “tradecraft,” “competencies,” “objectivity”—but too often delivers performance theater: analysts trained to look professional while making fragile inferences they cannot defend, cannot falsify, and cannot properly qualify.

This is not an argument that intelligence educators are lazy or that analysts are unintelligent. In fact, official critiques repeatedly describe analysts as dedicated and capable. The failure is structural: institutions optimize for throughput, uniformity, and measurable training completion rather than for the slow, bruising intellectual formation that real reasoning requires. Even when community-wide directives explicitly call for analytic rigor and critical thinking, the training pipeline has a habit of translating those mandates into “coverage” rather than mastery. ICD 610 defines critical thinking as a core competency—logic, analysis, synthesis, judgment, and systematic evaluation of multiple sources—expected across the workforce (Office of the Director of National Intelligence [ODNI], 2008/ICD 610 Annex B). ICD 203 frames analytic standards around rigor, integrity, objectivity, sourcing, and transparent reasoning (ODNI, 2015/ICD 203). And yet, the persistence of analytic failures, the uneven quality of products, and the recurring institutional reliance on “assumption-shaped inference dressed up as certainty” point to an inconvenient truth: stating standards is not the same as building thinkers.

If you want analysts who can withstand propaganda, detect disinformation, and avoid being used as unwitting amplifiers of deception, you do not get there by treating philosophy as an elective curiosity. You get there by rebuilding the intellectual spine of the profession: logic, epistemology (how we know), rhetoric (how influence works), ethics (what we owe truth and the public), and the disciplined habits that turn standards into behavior.

The Evidence We Keep Ignoring: “Critical Thinking” Is Mandated, Yet Still Thinly Taught

The Intelligence Community has formally acknowledged the centrality of critical thinking. ICD 610’s competency definitions explicitly place logic and judgment at the center of professional expectations (ODNI, 2008/ICD 610 Annex B). Yet recognition is not implementation.

One of the more candid discussions comes from scholarship addressing critical thinking in the Intelligence Community. Lengbeyer (2014) notes that analysts historically received only “one or two weeks” of critical thinking training—an absurd mismatch between the complexity of analytic work and the instructional time allocated to building reasoning skill. That is not a training plan; it is a compliance gesture.

The institutional response has often been to lean harder into tradecraft primers and structured analytic techniques (SATs) as if technique automatically produces judgment. The CIA’s Tradecraft Primer emphasizes making assumptions explicit, challenging mindsets, and applying structured techniques (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], 2009). The DIA has a parallel primer intended to support analyst training and provide quick reference methods (Defense Intelligence Agency [DIA], n.d.). These documents are useful. They are not sufficient. Tools do not substitute for intellectual formation any more than owning a gym membership substitutes for strength.

Even the broader education-and-training literature warns about overreliance on SATs. Kilroy (2021) argues that an overemphasis on structured techniques in some intelligence-analysis coursework may fail to provide the critical thinking skills needed to anticipate strategic surprise. That is a polite academic way of saying: we’re teaching procedure faster than we’re teaching judgment.

If your institutions claim to prepare analysts for strategic warning, influence operations, and adversarial deception—while delivering reasoning instruction measured in days—you have designed a system that cannot keep its promises.

The Core Defect: Intelligence Training Treats Knowledge Like a Product, Not a Problem

Intelligence analysis is not merely information processing. It is knowledge production under contestation. That means epistemology is not optional—it is the job. Heuer’s classic Psychology of Intelligence Analysis remains one of the clearest public statements of the cognitive hazards: mental models shape perception, ambiguous data invites premature closure, and analysts routinely assimilate new information into existing beliefs (Heuer, 1999). The book exists because the profession has long known that “smart people” still reason badly under uncertainty without disciplined methods and metacognitive controls.

What’s striking is not that the community lacks awareness; it’s that institutions keep acting as though awareness equals capability. The CIA’s own materials now explicitly explore epistemology as a way to enhance analysis. A 2025 CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence piece, for example, directly argues that epistemological principles can strengthen analytic methods and improve assessments—essentially admitting that the philosophical foundations matter for tradecraft outcomes (CIA, 2025).

So here’s the indictment: if your own intellectual infrastructure recognizes epistemology’s relevance, but your standard training pathways still treat philosophy and rigorous reasoning as peripheral, you are choosing institutional convenience over analytic competence.

Real-World Consequences: The Profession’s Greatest Public Failures Were Reasoning Failures

When intelligence fails in public view, the postmortems routinely reveal not just missing data, but broken thinking: untested assumptions, weak inferential hygiene, and a failure to communicate uncertainty honestly.

The 9/11 Commission famously identified a “failure of imagination” as a central defect—leaders and institutions did not sufficiently conceive of plausible threat pathways, despite signals in the environment (National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, 2004). “Imagination” here is not creativity as entertainment; it is disciplined scenario thinking, alternative hypothesis generation, and the willingness to challenge default frames. That is philosophy in action: questioning premises, exploring possibility space, and resisting complacent realism.

The WMD Commission’s critique of Iraq WMD assessments was even more damning: analytic products were described as loosely reasoned, ill-supported, and insufficiently candid about how much rested on inference and assumptions (Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction, 2005). In other words, the community produced conclusions that read like knowledge while being structurally closer to belief—belief protected by institutional momentum.

Lengbeyer (2014) connects this directly to critical thinking and method—highlighting how analysts became “too wedded” to assumptions and how tradecraft reform efforts aimed to improve reasoning transparency (e.g., assumption checks) (Lengbeyer, 2014).

These are not niche academic complaints. They are official, historic, high-consequence demonstrations of what happens when a profession confuses tradecraft familiarity with intellectual competence.

Why Training and Certification Pipelines Keep Failing: Incentives Reward Completion, Not Mastery

The education-and-training ecosystem is shaped by predictable bureaucratic incentives: standardization, scalability, documentation, and defensibility. Those incentives are not evil; they are managerial realities. But they produce a damaging outcome: institutions prefer what can be easily delivered, easily tested, and easily recorded.

That means slide-based instruction, shallow “definition familiarity,” and technique catalogs outperform the slow work of teaching argument evaluation, probabilistic reasoning, epistemic humility, and adversarial rhetoric. It also means assessments drift toward what is easy to score at scale. Multiple-choice testing can detect vocabulary recognition; it is far less effective at detecting whether someone can construct and critique an argument, identify inferential gaps, or appropriately qualify uncertainty.

Marangione (2020) discusses the challenge of evaluating and testing critical thinking in prospective intelligence analysts, highlighting how critical thinking predicts performance beyond general intelligence—and also how assessment itself is complicated and frequently flawed when treated simplistically. The point is not that assessment is impossible; it is that lazy assessment produces false confidence.

Walsh (2017) argues that intelligence education lacks a robust evaluation research agenda to validate workplace effectiveness of training and education programs—meaning institutions can keep “teaching” without proving they are improving performance. That is how underpowered curricula survive: nobody is forced to demonstrate outcomes.

Kilroy (2021) adds another layer: even when structured techniques are taught, the emphasis can crowd out the underlying critical thinking that makes techniques meaningful. In plain English: SATs become ritual. Students learn to “show work” without learning to do the work.

The Missing Disciplines: Logic, Epistemology, Rhetoric, and Ethics

If institutions were serious about producing analysts resistant to manipulation, they would treat the following as foundational rather than elective:

Logic and informal fallacy detection, not as trivia but as daily analytic hygiene. ICD 610’s competency language includes logic, synthesis, and judgment, yet many pipelines still fail to require sustained practice in argument evaluation (ODNI, 2008/ICD 610 Annex B).

Epistemology, because intelligence is a claim about reality under uncertainty. The CIA’s own 2025 discussion of applying epistemology to analysis underscores that epistemic principles can directly enhance analytic methods.

Rhetoric and persuasion, because propaganda and disinformation do not “beat” analysts by being true; they beat analysts by being psychologically and socially effective. Analysts who cannot identify persuasive architecture (framing, narrative hooks, emotional leverage, authority mimicry) are analysts who will misjudge influence effects even when they correctly judge factuality.

Ethics and civic epistemology, because intelligence is not a private game—it shapes policy, liberty, and violence. ICD 203’s emphasis on objectivity and independence from political considerations is an ethical demand as much as a procedural one (ODNI, 2015/ICD 203).

When those disciplines are missing, institutions produce a predictable type: the “competent technician” who can complete templates but cannot defend conclusions under cross-examination. That analyst is especially vulnerable in modern information conflict because disinformation exploits precisely the gaps that philosophy trains you to recognize: weak definitions, ambiguous categories, hidden premises, motivated reasoning, and social proof.

Implications: What This Failure Costs the Nation

First, it degrades warning and anticipation. Strategic surprise is not prevented by collecting more data alone; it is reduced by analysts who can imagine plausible alternatives, update beliefs appropriately, and resist institutional inertia. Kilroy’s analysis of strategic warning education makes clear that technique-heavy approaches can miss the deeper critical thinking necessary for anticipating surprise.

Second, it increases policy risk. The WMD Commission showed how high-confidence public claims can be built on fragile reasoning, with catastrophic downstream consequences (Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction, 2005).

Third, it damages public trust. When intelligence is perceived as error-prone or politicized, the credibility reservoir shrinks. ICD 203’s focus on objectivity and analytic standards exists partly because trust is a strategic asset, not a public-relations accessory (ODNI, 2015/ICD 203).

Fourth, it creates an internal competence illusion. Certificates, course completions, and technique fluency can mask reasoning deficits. That illusion is dangerous because it makes institutions overconfident—precisely the mindset deception campaigns exploit.

Recommendations: What Serious Reform Looks Like

Make philosophy and reasoning non-negotiable in analyst formation. Require sustained instruction (not a week) in informal logic, probabilistic reasoning, epistemology of evidence, and rhetorical analysis. The point is not to produce academic philosophers; it is to produce professionals who can defend judgments and recognize manipulation. Heuer’s work shows why cognitive discipline must be learned, not assumed (Heuer, 1999).

Stop treating SATs as the center of gravity; treat them as tools downstream of thinking. Keep primers like the CIA and DIA tradecraft documents, but embed them inside a reasoning-first curriculum where students must argue, critique, falsify, and revise—not merely apply templates.

Upgrade assessment from recognition to performance. Use argument-mapping exercises, red-team critiques, structured debate, calibration testing, and graded analytic memos that require explicit premises, evidentiary weighting, and uncertainty statements. Marangione’s work underscores that critical thinking measurement is difficult—but also too important to fake with simplistic tests.

Institutionalize epistemology as tradecraft, not enrichment. The CIA’s own recent engagement with epistemology should not be a boutique intellectual exercise; it should be translated into standard education outcomes and reviewer expectations.

Create an evidence-based training evaluation regime. Training should be required to demonstrate performance improvement in applied tasks, not just satisfaction surveys and completion metrics. Walsh’s call for an evaluation research agenda is exactly the pressure the field needs if it wants to stop rewarding “activity” over outcomes.

Tie leadership promotion and certification to reasoning competence. If supervisors and senior reviewers cannot detect weak arguments, the system cannot self-correct. Standards like ICD 203 are only as strong as the evaluators applying them.

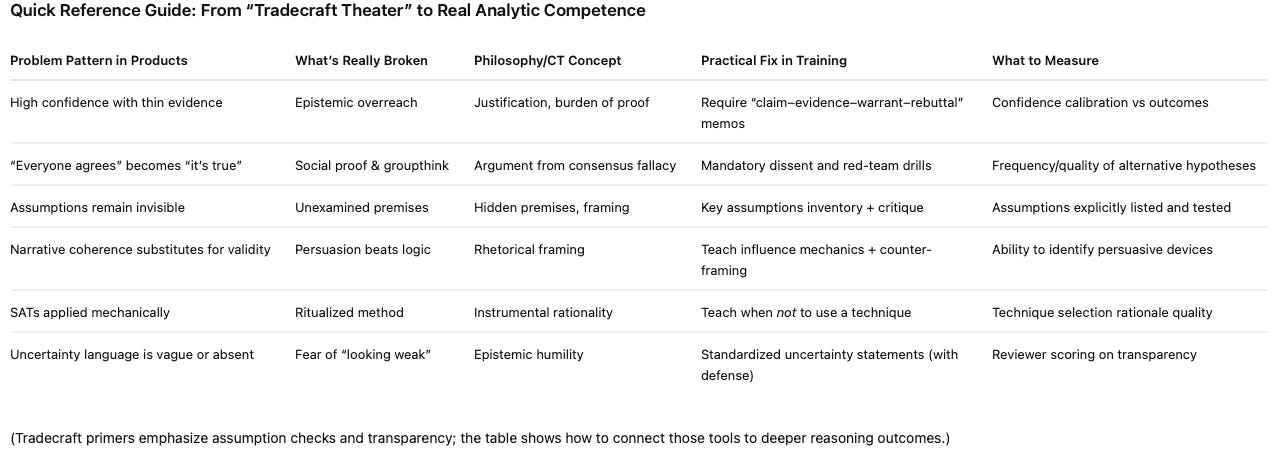

Quick Reference Guide: From “Tradecraft Theater” to Real Analytic Competence

Conclusion

The United States does not have an intelligence education problem because it lacks directives, primers, or competency libraries. It has an intelligence education problem because too many institutions still treat reasoning as an accessory rather than the core of the profession. ICD 610 can define critical thinking all day long; ICD 203 can mandate analytic standards; tradecraft primers can catalog techniques. None of that matters if the training pipeline continues to produce analysts who can perform tradecraft without understanding truth conditions, inferential validity, or the mechanics of persuasion.

The postmortems have been written. The cognitive hazards are documented. The need for imagination, rigor, and intellectual humility is historically established. The scathing conclusion is unavoidable: when institutions refuse to make philosophy and real critical thinking foundational, they are not merely failing students—they are manufacturing national-security risk.

Author Bio

Dr. Charles M. Russo is a veteran intelligence professional, educator, and author with over three decades of experience across U.S. military intelligence and the U.S. Intelligence Community, including analytic roles supporting national security missions. He teaches and writes on analytic tradecraft, critical thinking, and the ethical obligations of intelligence work, with a focus on strengthening judgment under uncertainty and resisting politicization and deception.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and professional-development purposes. It reflects the author’s analysis and interpretation of publicly available sources and does not represent official positions of any U.S. government agency, department, or element. No classified information is used or referenced.

References

Central Intelligence Agency. (1999). Psychology of intelligence analysis (R. J. Heuer, Jr.). Center for the Study of Intelligence.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2009). A tradecraft primer: Structured analytic techniques for improving intelligence analysis. Center for the Study of Intelligence.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2025). Applying epistemology to intelligence analysis (Center for the Study of Intelligence).

Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction. (2005). Report to the President of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Defense Intelligence Agency. (n.d.). A tradecraft primer: Basic structured analytic techniques.

Kilroy, R. J., Jr. (2021). Strategic warning and anticipating surprise: Assessing the education and training of intelligence analysts. Global Security and Intelligence Studies.

Lengbeyer, L. (2014). Critical thinking in the intelligence community. INQUIRY: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines, 29(2), 14–34.

Marangione, M. S. (2020). What’s thinking got to do with it? The challenge of evaluating and testing critical thinking in potential intelligence analysts. Global Security and Intelligence Studies.

Marcoci, A. (2018/2019). Is Intelligence Community Directive 203 up to the task? (Analytic standards and evaluation considerations).

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. (2004). The 9/11 Commission Report. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2008). Intelligence Community Directive 610, Annex B: Core competencies for non-supervisory IC employees at GS-15 and below.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2015). Intelligence Community Directive 203: Analytic standards.

Walsh, P. F. (2017). Teaching intelligence in the twenty-first century: Towards an evidence-based approach for curriculum design. Intelligence and National Security.